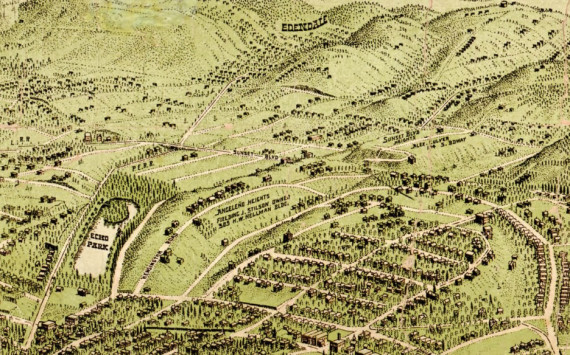

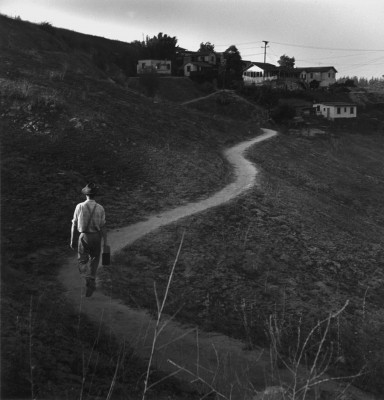

Early Barlow Hospital, unknown date

With all the hoopla surrounding Barlow Hospital these days, we thought we’d cover some of its 100-year-old history.

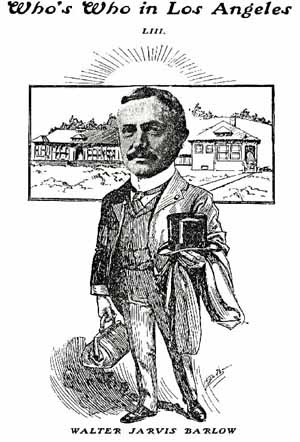

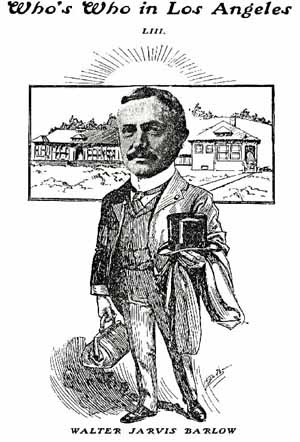

Barlow Hospital was founded in 1902 by Walter Jarvis Barlow. Born in Ossining, New York, Walter traveled to Los Angeles in 1897 seeking a dry, sunny climate after contracting tuberculosis. Though his was caught early and thus cured, tuberculosis was a serious disease treated with rest, fresh air, sunshine and general well-being. So Los Angeles became not only a perfect place for him to recover, but became the home of the area’s first tuberculosis treatment facility: Barlow Sanatorium.

Source: Barlow Genealogy

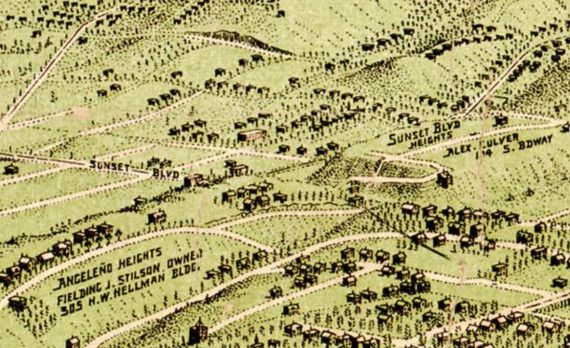

Set on the border of Elysian Park (which is the city’s oldest park, founded in 1886) were the 25 acres he purchased from J.B. Lankershim for $7,300. A $1,300 donation actual came from Alfred Solano, his namesake being, of course, nearby Solano Canyon. Walter was actually Solano’s step-son-in-law (Walter’s wife Marion’s mother was remarried to Alfred). Jarvis Street in Solano Canyon is likely named after Walter.

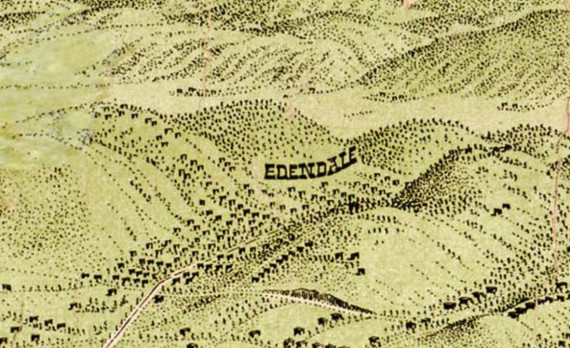

Anyways, enough about Walter. He created the Sanatorium to care for those people with turberculosis, a place for them to relax and get well. The site chosen for the hospital was a good one – a small valley protected the climate and provided clean air away from the bustling city nearby. Ironically, the Barlow Hospital website describes the location as wise because it was a “protective barrier against development.”

Most of the structures on the site (32 in all) were built between 1902 and 1952, and have been recognized as Cultural Monument No. 504. In addition to administrative and medical offices, there are quite a few patient bungalows with porches, dining rooms, laundry facilities, and recreation areas. If you’re walking South on Stadium Way from Scott Avenue, you can see these residential-looking structures on the right-hand side. You’ll also probably notice how dilapidated they are. Over the first few years, the hospital had enough room to house and care for 34 patients.

By the end of the 1970s, the focus on turbuculosis was no longer needed as TB became manageable and treatable, and instead concentrated on the treatment of respiratory diseases. By the 1980s, the hospital wanted to provide for AIDS patients by fixing up some of buildings that weren’t being used. Interestingly, the efforts came out of an organization that fought against a 1986 proposition that would have required a quarantine of AIDS carriers.

In 1988, the Chris Brownlie AIDS Hospice was opened at Barlow as the first AIDS hospice in California, and remained open until the mid-1990s. The two-story building where the hospice was had been home to around 1,500 patients.

The hospital has maintained its original philanthropic mission and continues to be a not-for-profit facility. It serves Southern California as a long-term acute care facility, focusing on rehabilitation goals such as weaning patients off of ventilators, and even home to the Barlow Respiratory Research Center. Currently, the hospital is seeking to sell of a huge portion of the land to fund the development of a new hospital, which it needs to do in order to comply with post-Northridge earthquake retrofitting requirements.

The future of the historic Barlow structures are uncertain, but we’ll be sure to keep you updated as they happen.